Keep Calm and Accelerate Erythropoiesis

/e·ryth·ro·poi·e·sis /iˌriTHrōpoiˈēsəs/ noun: the production of red blood cells.

Yesterday we saw that the air up in Albuquerque is about 15% less dense than a mile lower at sea level. It follows that every inhalation here contains 15% less substance: no matter how deeply you breathe, your blood just can’t pull quite as much precious oxygen from your lungs.

As a result, lowland visitors to the high desert often experience signs of mild hypoxia when they arrive. First day in town? Expect headache and fatigue, or, as some describe it, hangover symptoms. A vague feeling that you’re breathing too shallowly may make it hard to get a good night’s sleep. And even if you’re in great shape, a flight of stairs might leave you gasping for air.

Happily, Albuquerque is at the low end of “high altitude,” so there’s no risk of full-blown altitude sickness. Some extra water and rest should get you through your first few weeks, and in time even newcomers (like I was last fall) can breathe as easily as born-and-raised Burqueños.

How does your body adjust? Let’s break it down by day.

Day 1: Deeper Breathing

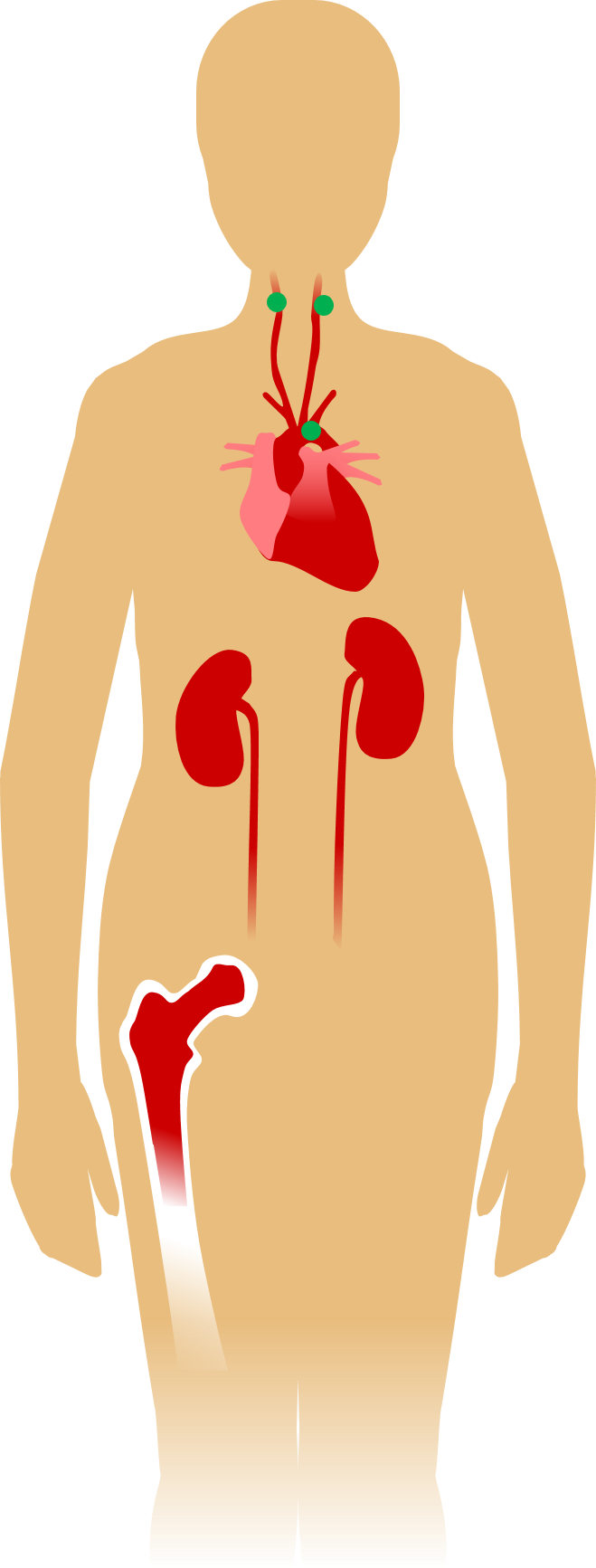

As soon as you hit thin air, you sense it in your heart. Seriously. In your neck, too: chemoreceptors in your aortic and carotid arteries (the green dots in the illustration) constantly monitor the partial pressure of O₂ in outbound blood. If it drops too low they signal the brain to accelerate and deepen your breathing. You probably won’t get too breathless here in Albuquerque unless you go for a full workout, though—at rest, twice our altitude is needed to really kick your respiration into high gear.

Days 2-3: A Boost in Blood Cells

On the other hand, a switch to 5,000 feet is enough to rev up your production of red blood cells, a.k.a. erythrocytes. The drop in arterial oxygen triggers a series of reactions in your kidneys of all places, culminating in production of more of the hormone erythropoietin (EPO). Like any good hormone, EPO heads for your bloodstream to target tissue elsewhere, in this case the red bone marrow in your pelvis, spine, ribs, skull, and long bones. This marrow is always at work on erythrocytes, but the bump in EPO spurs it to new levels.

Why erythrocytes? These tiny cells are essentially passive packets of the protein hemoglobin that ride laps of our circulatory system, collecting oxygen in the lungs and distributing it around the body. The key is hemoglobin’s ability to bond with O₂, which isn’t particularly water-soluble; a small amount dissolves directly into our plasma, but a whopping 98% of it needs to be scooped up and hand-delivered by hemoglobin. Running low on O₂? Increase the amount of hemoglobin in circulation, and you increase the amount of oxygen you bring to your tissues moment to moment.

Days 4-18: Your New Normal

Within two or three days of ascending to Albuquerque, you’ll have a higher hematocrit, meaning your blood will contain a measurably higher percentage of erythrocytes by volume. Well done, you! But you’re only just beginning.

For every new mile of elevation, the average body needs about 18 days to adjust. That’s 18 days of elevated erythrocyte production in your marrow, so if you’re moving up from sea level, do your bones a favor and eat plenty of iron in that time. Iron is the main raw material for all that new hemoglobin you need, and you can find it in red meat, beans, spinach, and other fortified foodstuff. Bon appétit!

Day 19 and beyond...

By now your hematocrit has probably plateaued at a new, higher normal. Congratulations, you’ve acclimatized!

Or at least, your blood has. Some high-altitude immigrants feel the fatigue of altitude adjustment for another couple months as their bodies continue to adapt with, for example, capillary angiogenesis in skeletal muscles (which brings more blood to the tissue), increased myoglobin synthesis (which distributes the oxygen more efficiently within the muscle), and production of more mitochondria (which uses oxygen more efficiently by increasing sites of cellular respiration).

Even after your body has adjusted in every possible way, you may never be able to exercise as intensely at altitude as you do at sea level. A light jog in the high desert can jack your breathing and heart rate up to the same levels as a sprint once did—it’s not that you’re out of shape, there’s just an upper limit to the oxygen available. Although some athletes train at high elevations in the hopes of developing their physiological efficiency, their efforts can be counterproductive if the thin air keeps them from working out as hard as they would seaside. Dreaming of an Olympic gold? Consider living in thin air but exercising at a lower elevation to get the best of both worlds.

And always treat your impressively adaptive body right with lots of rest, fluids, and nutritious food. Speaking of which, how’s your favorite lowland recipe going to work up here? We’ll be back tomorrow to talk about the chemistry of cooking in a high-altitude kitchen.

This post was brought to you by Human Physiology: An Integrated Approach (Fourth Edition) by Dr. Dee Unglaub Silverthorn, High Altitude: Human Adaptation to Hypoxia by Drs. Erik R. Swenson and Peter Bärtsch, and a few high-iron spinach salads.