Beautifully Burnt Earth

/It’s no wonder that Pueblo pottery is considered some of the most beautiful in the world: the Pueblo people have been refining their techniques for over a thousand years. These days there are nineteen Pueblo tribes with land strung like a beaded necklace across northern New Mexico, and each boasts artists who hand-sculpt and fire clay pots according to their own local (and personal) styles. How are they able to craft such a wide variety of smooth, matte, slick, and colorful pieces using only materials found in the ground around here?

Whatever the peculiarities of each potter’s process, the first ingredient is always clay—but as familiar as that material may seem to the layperson, you may be hard-pressed to define what clay is exactly, let alone how it works. Let’s take a closer look at the chemistry behind this craft.

According to the phi scale, clay is any sediment whose particles are smaller than 3.9 micrometers (µm). This means the exact composition varies from place to place, but there is some consistency in that only certain types of rock break down to that degree. Some minerals (like quartz and selenite) tend to erode into crunchy grains of sand; others (varieties of feldspar like kaolinite) weather all the way down to particles so fine they feel like soft mud.

Phi Scale of Sediments

> 256 mm = boulder

64 - 256 mm = cobble

2 - 64 mm = gravel

62.5 µm - 2 mm = sand

3.9 - 62.5 µm = silt

< 3.9 µm = clay

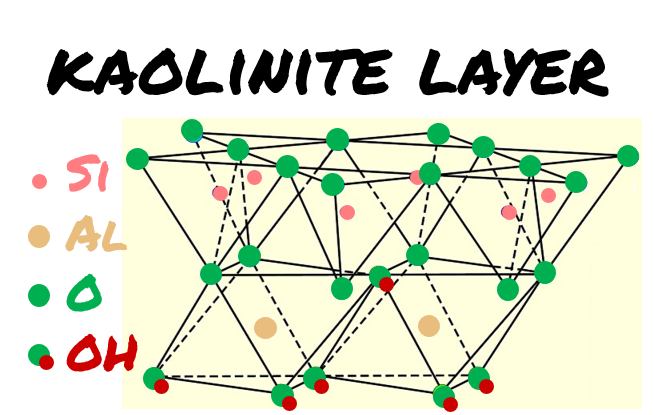

Thus kaolinite clay is the main ingredient in pottery. Zooming down to the molecular level, we see kaolinite is composed of equal parts silicon and aluminum oxides layered in sheets that are held together by hydrogen bonds. Out in nature it readily absorbs rainfall to become slurry-like, then sun-dries back into powdery shards. This softening and hardening is easily repeated day after day, year after year, because it amounts to physical changes as opposed to chemical reactions. Water comes and goes, but the underlying structure of the clay stays the same.

Put kaolinite in a kiln, though, and you can give it a permanent solidity by rearranging its chemical bonds. At about 500°C, the weak hydrogen bonds between layers break and are replaced by stronger oxygen bonds. H₂0 is released as a byproduct and the oxides are pulled together more tightly in its absence—that is, the clay shrinks slightly while steam sweeps away.

At this stage the pot is irreversibly baked but still too brittle to be useful because of its layered structure. Happily, the Pueblo method of firing clay usually achieves a maximum temperature of between 625 and 950°C, so their pottery strengthens further. At such heats the oxides lose their layers and meld into an amorphous metakaolinite that forms oxygen bonds not just up and down between sheets but in all directions.

These principles apply in pottery-making around the globe, but here in the Southwest Pueblo potters reach these high temperatures in outdoor kilns that they build from scratch for each firing. First they set up a metal grate with some air flow beneath it, often by propping it on bricks. Hand-coiled pots are tightly arranged atop the grate while cedar sticks go beneath it to serve as kindling. A layer of broken potsherds shield the raw clay from the fuel so it doesn’t heat unevenly, which can cause it to discolor, warp, or even explode.

Potters then constructs a dome of scrap metal around the grate to keep in heat, leaving gaps for air to flow in and maintain oxidation throughout the firing (that is, allow oxygen to keep breaking hydrogen bonds and scoop hydrogen out of the clay as newly-formed steam). Finally, they cover the dome with cow or sheep dung to serve as fuel and light the whole structure on fire. Part of the art of making pots is carefully maintaining the fire at an appropriate level of even heat for several hours and determining when the clay has cooked sufficiently—even though the potters can’t see or touch it at any point in the process. This intuition is acquired through years of practice and is a point of pride for accomplished artists.

Another point of pride is the coloring potters can achieve through the use of particular clays and slips (clay suspended in water to form a liquid paint or paste). Pure kaolinite makes for whitish clay, but it’s rarely pure in nature, and Pueblo artists use that to their advantage. Generation by generation, expert potters have passed down the sometimes secret locations of deposits colored with different impurities. Iron, copper, and cobalt render clay red, yellow, brown, and black; in northern New Mexico, high mica contents lend clay a metallic luster that distinguishes the pottery of the Taos and Picuris Pueblos. By crafting yucca brushes and watering clays down into slips, artists can paint layers of color onto a pot’s surface and produce geometric designs or images from nature.

Certain colors and textures can also be achieved during the firing process itself. The Santa Clara and San Ildefonso Pueblos in particular are renowned for their pottery’s rich black gloss. Potters achieve this by smothering the fire with horse manure in the final stages, sealing off air gaps and eliminating oxygen within the oven. This creates a reductive atmosphere in which carbon monoxide builds up and reacts with iron on the pots’ surface, rendering it a deep black (and giving off a lot of smoke in the process).

There are so many factors at play in pottery-making, from the clay’s mineral composition to the fuel’s water content to the gusts of cool or warm wind that may surprise a potter on firing day, that it’s almost impossible to treat it as an exact science. The laws of chemistry may underlie the process, but only a skilled artist can intuit moment to moment what’s needed to guide the creation of a perfect pot. Here’s hoping the Pueblo traditions continue to thrive and evolve for the next thousand years as well.

This post was brought to you by the Royal Society of Chemistry, Caveman Chemistry, the Lowell D. Holmes Museum of Anthropology, and the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center here in Albuquerque (including the delicious frybread at their Pueblo Harvest Cafe).